-40%

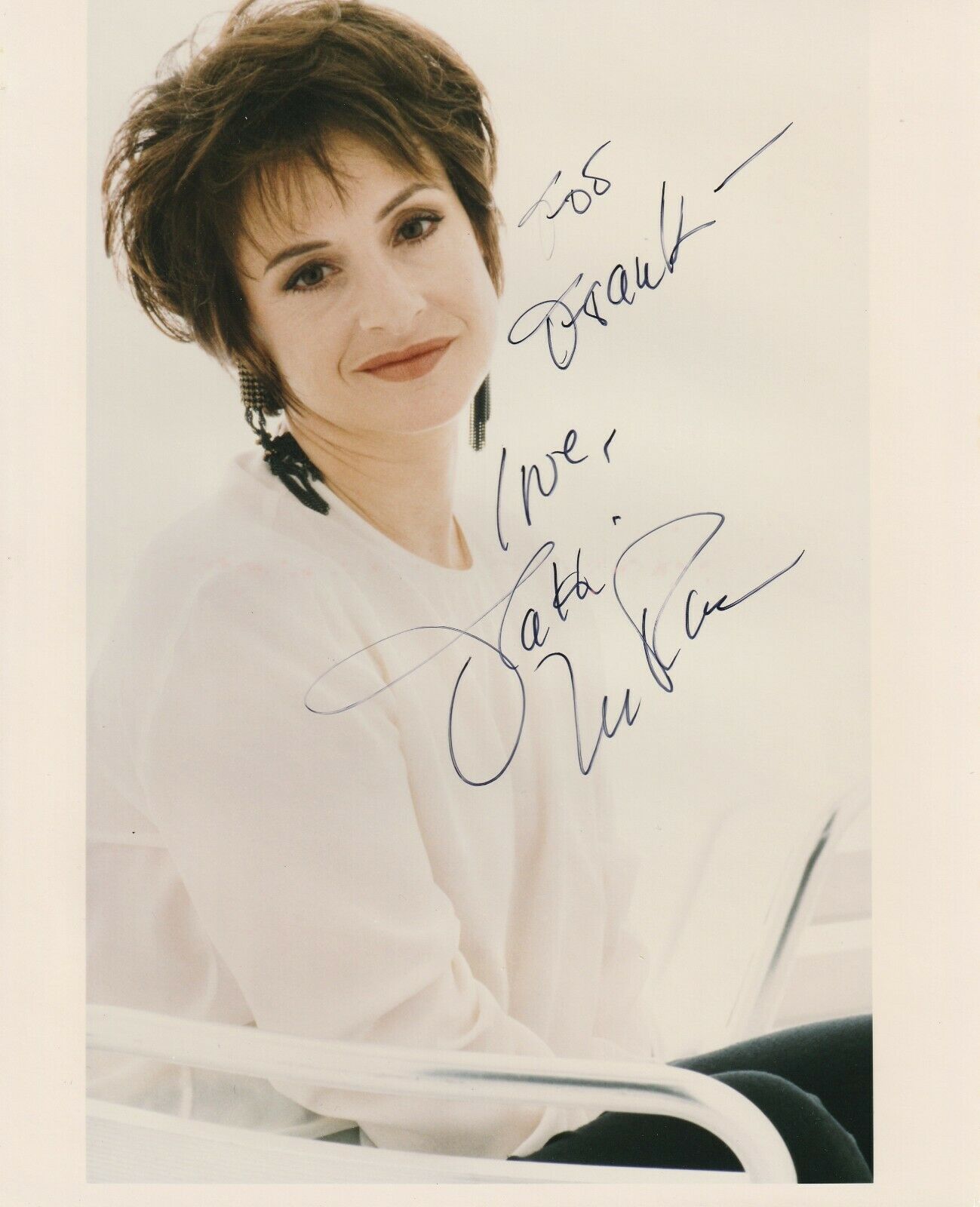

Tragic Stage/Screen Star Jeanne Eagels Orig. 1910s Elegant Edwardian Photograph

$ 7.63

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

ITEM: This is a c. 1910s–early 1920s antique and original photograph of tragic stage and screen actress Jeanne Eagels. A former Ziegfeld Girl, Eagels went on to greater fame on Broadway and in the emerging medium of sound films. She is photographed here by New York City's Moffett Studio and is an elegant and stylish Edwardian beauty!During the peak of her success, Eagels began abusing drugs and alcohol and eventually developed an addiction. She went to several sanatoriums in an effort to kick her dependency. By the mid-1920s, she had begun using heroin. When she entered her 30s, Eagels began suffering from bouts of ill health that were exacerbated by her excessive substance abuse. Her career, already burning itself out, ended abruptly with her death from a heroin overdose at the age of 39. Her volatile persona instantly became the stuff of legend.

Photograph measures 7.5" x 9.5" on a matte double weight paper stock. The photographer's blind stamp is in the bottom right corner. Handwritten notations on verso.

Guaranteed to be 100% vintage and original from Grapefruit Moon Gallery.

More about Jeanne Eagels:

Jeanne Eagels, one of the most intriguing stars of late silent films and the early talkies, was born Amelia Jean Eagles on June 26, 1890 in Kansas City, Missouri, to Edward and Julia Sullivan Eagles. Young Jean was part of an impoverished family of eight, with three brothers and two sisters. She likely stopped going to school when she was 11 years old.

As a girl, she decided to become an actress after appearing in a Shakespearen play. Of that performance, she said, "I played the grave-digger in 'Hamlet,' first, at the age of seven. They gave me the chance to play Shakespeare because nobody else of the tender age of seven would do so. They wouldn't say the rather amazing words...the other kiddies. I took it all quite seriously and said ALL the words without a quiver. Once I had begun I could not be stopped. I was ill when I was not on the stage. It seemed to me I couldn't breathe in any other atmosphere."

She followed up the experience up by playing bit parts in local theatrical productions. When she was 12 years old, she became a member of the Dubinsky Brothers' traveling stock company, appearing at first as a dancer, but eventually working her way into speaking roles. Eagels soon was playing leading roles in the stock company's repertory, including "Camille," "Romeo and Juliet," and "Uncle Tom's Cabin." Later, a myth arose that Eagels' began her career as a circus performer. The 1957 biographical film "The Jeanne Eagels Story" erroneously depicts Eagels' beginning as a hootchie-kootchie dancer in a carnival. The Dubinsky Brothers did use a tent to put on their shows, but they did not present carnival acts but performed popular comedies, musicals, and dramas. The tent was only used during the spring and summer months, while during the colder months, the company performed in theaters and halls in the Midwest.

Jeanne Eagels married the scion of the Dubinsky family, Morris, the oldest of the brothers. She was likely in her teens, and probably had a baby by Morris. Stories about Eagels' past diverge, and in one account, the child was adopted by family friends, while in another, Eagels' baby boy died in infancy, triggering a nervous breakdown for the bereft mother. Eagels and Dubinky separated, likely due to his infidelity. Jeanne eventually left the Dubinksy company and joined another touring stock company, which eventually brought her to New York City.

Eagels decided to make herself over in New York as she fought her way up in the fiercely competitive theatrical world. A brunette, Eagels dyed her hair blonde and said that she was of Spanish and Irish lineage, and that her surname was originally "Aguilar," which loosely translates into English as "eagle." She changed the spelling of her name from "Eagles" to "Eagels," reputedly as she thought it looked better on a marquee. Eliminating her past, she presented herself as an ingÃffÃ'©nue rather than as a divorced woman and mother of a dead infant. She also adopted an English accent as David Belasco, the legendary theatrical impresario, had commented that she spoke like an "earl's daughter."

She began her climb up the greasy pole of Broadway stardom by appearing as a chorus girl. She even served a stint as a Ziegfield girl, but Eagels was determined to establish herself as a dramatic roles, wining bit parts in the plays "Jumping Jupiter" and "The Mind the Paint Girl."

Eagels took a trip to Paris, where she likely studied acting with Beverly Sitgreaves, an expatriate American actress who had appeared with Sarah Bernhardt, Eagels' idol. After Jeanne Eagels' death, there arose a myth that she was a "raw," untrained talent who just happened to have the spark of genius on stage. This is demonstrably false as she had a thorough grounding in technique in her six-year apprenticeship in regional stock companies. She also studied acting with Sitgreaves and with acting coaches in New York. The myth likely is rooted in the biography of Eagels' stage co-star Leslie Howard that was written by his children. Howard was of the opinion that Eagels was untrained, but that likely was rooted in English snobbery vis-ÃffÃ'Â -vis America actors as he had the same opinion of the great Bette Davis. What Howard likely meant that the emotionally erratic Eagels was undisciplined rather than untrained. George Arliss, considered one of the great stage actors at the time he appeared on Broadway with Eagels, would hardly have chosen her to appear in three of his productions if she were not trained and up to giving a fine performance. Arliss was full of praise for Eagels.

In Paris, Eagels attracted the attention of Julian Eltinge, the famous Broadway female impersonator, though they were not introduced. Ironically, when he returned to New York, Eltinge found out that Eagels was to be his co-star in what turned out to be a long tour of the play "The Crinoline Girl." The two became good friends.

Eagels won the role of a prostitute who becomes a faith-healer in the touring company of the play "Outcast" by modeling herself after the play's star, Elsie Ferguson, for her audition. She won the part, and also won great reviews during the tour's swing through the South. When the touring company returned to New York for an off-Broadway engagement, some critics were there to see if Eagels actually did live up to the road reviews of her "Outcast" performance. She did, and the critics were suitably impressed.

The Thanhouser Film Co. cast Eagles in the film of "Outcast" in 1916, which was entitled The World and the Woman (1916) upon its release. Eagels was working during the daytime in films and at night on the stage. Suffering from fatigue and insomnia, she sought treatment and likely became hooked on drugs during this period. With the aid of physician-prescribed dope, Jeanne Eagels continued her hectic dual-career of making movies during the day while acting on stage at night. The routine continued until 1920. Suffering from chronic sinusitis and other maladies, Eagels descended the slippery slope of self-medicating her ills, an unfortunate situation exacerbated by her fondness for drink.

Eagels received great reviews when she starred with George Arliss in the Broadway hit "The Professor's Love Story" in 1917. She followed up their joint triumph with two more co-starring ventures with Arliss, "Disraeli" and the even-more-popular play "Hamilton." Of his co-star, Arliss said that each of the three distinctly different parts she acted were "played with unerring judgment and artistry."

In 1918, she appeared in Belasco's production of "Daddies," an original play about the plight of war orphans starring George Abbott. She quit the hit show either due to exhaustion or because, as rumor had it, she was fed up with Belasco's sexual harassment, though she praised him as a producer.

"Often in the theater there is a feeling of commercialism in every detail; it may not touch one directly, but it is there, and the consciousness that the financial success of the play is perhaps of first importance is decidedly unpleasant. Now, Mr. Belasco puts acting, like every other element of a production, upon an artistic basis. He makes you feel that a thing is important artistically or not at all. Money seems never to be a consideration, yet the making of it follows as a result of making the production as nearly perfect as possible.... That point of view on the producer's part means a great deal to the actor; it leaves him free to do so much, and is an incentive to work toward a faithful portrayal of character. To me everything about Mr. Belasco's theater points toward that one ideal of his -- perfection."

She next appeared in the comedy "A Young Man's Fancy" (1919), followed up by "The Wonderful Thing" (1920). By the time she appeared in the latter, a modest success that played for 120 performances, she had become a true Broadway diva, having to wait for the applause to die down after her entrance before she could deliver her lines. She had her own distinctive ideas on how to give a fresh impression to the audience for each performance:

"Audiences mean as much to an actress as the acoustics of a concert hall mean to a musician. The musician must vary his playing according to his acoustics--according to the sort of room in which his concert is given.... A sort of sixth sense enables me to discern the character of an audience within a few minutes after I have begun to play, and it is only the people for whom I am making this lovable girl live at that one performance that matter. Former audiences are swept from my thought as though they had never been. As far as the audience of the moment is concerned others have never been. What I have done, or have not done, for them doesn't matter to the folk who have come to see the play to-night. I am so very conscious of this that I am able to play to them as though I were creating the part for the first time... I do wrong in speaking of 'playing to an audience,' however. A true artist never 'plays to the audience.' Rather he or she keeps his or her own vision true, and the creation evolves itself."

Her next Broadway appearance, "In the Night Watch" (1921), was another modest success, but she soon was to appear in the play that would make her lasting reputation. The opportunity came her way when another actress turned down the role of the prostitute Sadie Thompson in the theatrical adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham's short story "Rain."

On the road in Philidelphia, the play received discouraging reviews, necessitating a rewrite of the second act. By the time the rewritten "Rain" debuted on Broadway on November 7, 1922, at Maxine Elliott's Theatre, all the kinks had been worked out, and the play was a smash, running for 256 performances. When the company returned to Broadway after the road show, re-opening at the Gaiety Theatre on September 1, 1924, "Rain" starring Jeanne Eagels ran for another 648 performances, transferring to the New Park Theatre on December 15, 1924. "Rain" elevated Jeanne Eagels into the pantheon of American theater greats.

John D. Williams, the director of "Rain" said, "In my score of years in the theater Miss Eagels was one of the two or three highest types of interpretive acting intelligences I have met. To work with her on a play was once more to feel one's self in the theater when it was in its finest estate; when a play was not a 'show,' nor even a performance, but a work, which because it had something to say that might clarify life, was a living thing and simply demanded to be heard. It was then that somebody, known or unknown, wrote something that deserved fanatically true fulfillment--and somebody else of magic touch acted it.... Miss Eagels had that touch of magic in character interpretation- the quick exchange of ideas as to the sense of the scene. And then would come the superbly tragic entrance, for example, of Sadie Thompson in the last act of 'Rain,' with its flawless blend of bitter disillusionment, irony, revenge, terror."

Eagels' great performance was acknowledged as responsible for the great success of the play, and although Gloria Swanson had some success playing Sadie in the silent movie version of the play in 1928, Joan Crawford did less well in the role in the 1931 talkie version. Both Swanson and particularly Crawford were upstaged by their leading men, Lionel Barrymore and Walter Huston, respectively. Rita Hayworth's version in 1953, opposite José Ferrer, is barely remembered. Sadie Thompson belonged to Jeanne Eagels, and the touring company of "Rain" toured for four years.

In 1917, Eagels had said, "I am timid and afraid of men and far too busy to become well acquainted with them. My work fills my life, and I should not care to fall in love or marry before I am very, very old -- about thirty-five -- because a woman gives too much of herself when she loves, and that would interfere with her career."

By the time Eagels married her second husband, the stockbroker Edward H. Coy, in 1925 at the age of 35, she had developed a reputation as a temperamental actress who was a hard drinker. Coy had achieved Ivy League gridiron immortality as a 6-foot, 195-pound fullback at Yale, where he was named an All-American in 1908 and 1909 but had turned to the sauce for solace now that the cheers had faded. The incompatibility between the two did nothing to ameliorate her problems with her mood swings or with drink.

After "Rain," she took time off, either turning down offers such as the role of Roxie Hart in "Chicago" (1926) or quitting plays she did sign up for during rehearsals. Finally, she made her Broadway return in the George Cukor-directed light comedy "Her Cardboard Lover" (1926) opposite Leslie Howard. Broadway critics and audiences had grown accustomed to Eagels in more substantial fare, and on opening night, it was Leslie Howard whom the audience cheered, calling for Howard to take curtain calls. Controversially, Eagels took Howard's curtain calls, thanking the audience "on behalf of my Cardboard Lover." The critics, too, wound up praising Howard rather than Eagels.

Eagels fondness for medicating herself and for drink caused problems during the run of the show. Her on-stage behavior could be egregious, as when she stepped out of character and, thirty for the sauce, asked Howard's character for a drink of "water." This caused the stage manager more than once to bring down the curtain during a performance, and Howard left the stage in a huff at one point.

About bad acting, Eagels blamed it on "...[N]ot being a good listener. So few people are. For instance, when you and I are talking here and I say 'no' very deeply and quietly, your reply will be 'yes' with something of a rising inflection, a lighter modulation. You have listened to me and have made a correct tonal reply. On the stage, most of the actors and actresses know their cue words and take their cues, but they haven't listened to the speech preceding their own. The result is a correct enough answer as to word, but not as to tone. There is not tonal intelligence in the reply. Good listeners...so rare."

John D. Williams, her director in "Rain," attributed her greatness on the stage to her great ability to listen while on stage.

"First off, she knew to perfection, and adhered to as to a religion, the art of listening in acting. At every performance, whether the first, or the hundredth, the speeches of the character addressing her were not merely heard but listened to. Hence there was always thought and belief and conviction behind every speech and scene of her own-- the essence of theater illusion."

The drink and drugs apparently were eroding that greatness. However, despite her on-stage antics, "Her Cardboard Lover" was another modest success, playing for 152 performances. After shooting the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film Man, Woman and Sin (1927) with John Gilbert, she toured with the play in the large cities.

Eagels' behavior during the filming of Man, Woman and Sin (1927) was atrocious. Gilbert, whom she reportedly had an affair with, said Eagels was the most temperamental actress he had ever worked with. She would appear late at the studio, and once, she disappeared for several days. The Hollywood trade press credited Eagels disappearance to a drink binge, and at one point, she took off on a two-week vacation to Santa Barbara without informing her director, Monta Bell. Bell asked studio management to terminate Eagels' contract, which they did. Fortunately, there was enough footage so Bell could salvage the film without re-shooting.

John Gilbert said of Eagels, "She seemed to hate the movies for a popularity they could not give her....[The] blind, unreasoning adulation of the movie fans was a type of popularity she spurned. Fundamentally, Jeanne was much superior to us. Movie actors are crazy to be worshiped. Jeanne Eagels wanted to be understood and appreciated."

When the film was released, Eagels' performance received mixed reviews, but the picture was a failure primarily due to the poor reviews garnered by Gilbert. Critics rejected the great lover playing a naive mama's boy in this film. Gilbert's career was salvaged shortly thereafter by the release of his second film with Great Garbo, Love (1927), which was a smash hit at the box office.

When Eagels began touring the East Coast in "Her Cardboard Lover," the Boston engagement was cut in half to one week as Eagels reportedly was ill. After the play moved to Chicago with a revivified Eagels, she divorced Coy in 1928, citing physically abuse and accusing him of breaking her jaw. Eagels claimed that Coy had threatened to wreck her budding movie career by ruining her face. Coy, a heavy boozer like his soon-to-be ex-wife, pleaded no contest and the divorce was granted.

The Mid-Western tour of "Her Cardboard Lover" moved on to Milwaukee, but Eagels was a no-show at both the Milwaukee and the subsequent St. Louis performances. She claimed that she was suffering from ptomaine poisoning, but eye-witness accounts placed her in Chicago on a long boozing binge when she was supposed to have been in Milwaukee. Her indefensible and unprofessional behavior brought her an 18-month suspension from Actor's Equity, which banned her from performing on stage with any other Equity actor for the length of the suspension. The ban essentially ended her stage career in New York and the rest of the country, although it could not stop her from appearing by herself on stage in non-Equity venues. Eagels hit the vaudeville circuit, performing scenes from "Rain." She also appeared in movies as producers were desperate for trained stage people with the advent of sound, and she eventually made more money from the film industry and vaudeville than she ever had from the "legitimate" stage.

Ironically, it was Monta Bell, now working at Paramount's Astoria Studios in New York, who hired Jeanne Eagels for her film comeback. In 1929, Bell announced that even though Equity didn't want Eagels, he wanted her, for she had been the consummate professional during the making of Man, Woman and Sin (1927). The man who had urged the MGM brass to fire her now told the press that he had actually urged MGM to sign Eagels to long-term contract for more pictures.

The first movie Eagels made for Paramount was the Monta Bell-produced The Letter (1929), which reunited Eagels with W. Somerset Maugham. Katharine Cornell had had a Broadway hit with Maugham's play as the murderous adulteress, and Eagels delivered an electrifying, legendary performance in the role on film. After Eagels received rave reviews for her The Letter (1929), Paramount took Bell's advice and signed her to a contract for two more pictures, Jealousy (1929) and The Laughing Lady (1929).

She began shooting "Jealousy" (1929) with the English actor Anthony Bushnell, whom she had hand-picked to be her leading man, but during filming it was apparent that Bushnell's voice was not registering well on the sound equipment. Bushnell was replaced by the up-and-coming star Fredric March, who later said Eagels was "great" to work with, but that the movie they made together was a "stinker." There were rumors that Eagels had suffered a nervous breakdown while filming "Jealousy", but Paramount denied there had been any trouble with their new diva. However, Eagels asked to be let out of her contract for "The Laughing Lady" on the grounds that she was either ill or because she didn't like the script, and the studio obliged, replacing her with Ruth Chatterton.

About her management of her personal affairs, Eagels said, "I cannot bear to transact any of my own business or make any of my own professional arrangements. I have an aversion to it I cannot overcome. I can't read the papers, either. Mention of my personal life, even tho I expect it, acts terribly on my nerves. I suppose I'm an odd person."

It was reported that now that the Actors Equity ban was due to expire in the fall of 1929, Eagels was preparing to return to Broadway. In September, Eagles underwent successful surgery to treat ulcers on her eyes, a condition was caused by her sinusitis. Two weeks after surgery, on the night of October 3, 1929, as Eagels was preparing for a night out on the town, she fell ill and was taken to a private 5th Avenue hospital. In the hospital waiting room, she suffered a convulsion and died.

Three autopsies were conducted over the following three months and reached three different conclusions as to the cause of her death, which was variously attributed as an overdose of alcohol, the tranquilizer chloral hydrate, and heroin in the successive autopsy reports. All three substances likely were in her system when she died, and it was suggested that the unconscious Eagels had received a sedative from the first doctor to treat her, and that subsequently a second doctor, not knowing she had already been sedated, had unknowingly given the unconscious actress a second shot, thus causing the overdose that killed her.

When her estate went through probate, it was worth an estimated ,000 (approximately 2,000 in 2005 dollars) after her debts and funeral costs were deducted. Dying intestate, the estate went to her mother. A wake was held at Campbell's funeral home in New York City, the same establishment that had handled Rudolph Valentino's funeral. Reportedly, her movie "Jealousy" was playing across the street from the funeral home as she lay in her casket, finally at peace. Her body was sent to Kansas City, where a Catholic mass and requiem was held, and she was laid to rest with her father and a brother.

Eagels was posthumously nominated for a 1929 Best Actress Academy Award for her role in "The Letter," the first actor to be so honored. She lost out to superstar Mary Pickford, one of the founders of the Academy, who took the Oscar home to Pickfair for her performance in "Coquette," her first talkie.

Jeanne Eagels' life was limned in the 1957 film _Jeanne Eagels_, which starred Kim Novak. This film is fictionalized biography that whitewashed the truth about Eagels' life. In recent years, there have been rumors that Eagels enjoyed same-sex relationships with other women, but the rumors remain unsubstantiated. In her lifetime, she was romantically linked to many famous men, including the conductor Arthur Fiedler, the gambler "Nick the Greek" Dandalos, and the theater critic Ward Morehouse. She was pursued by producer David Belasco, theater owner Lee Shubert, and the Prince of Wales, the future Duke of Windsor.

About actors, Jeanne Eagels was quoted as saying, "We are glorious, unearthly people, set above all others because of our genius, our capacity to sway others, to make them laugh and cry, or make them live a romance we but play." In the Academy Award-winning All About Eve (1950), writer-director Joseph L. Mankiewicz has the critic Addison DeWitt tell the great fictional diva Margo Channing (played by Leslie Howard's other great "untrained" co-star, Bette Davis), "Margo, as you know, I have lived in the theater as a Trappist monk lives in his faith. I have no other world, no other life -- and once in a great while I experience that moment of revelation for which all true believers wait and pray. You were one. Jeanne Eagels another."

The actor playwright Noël Coward said, "Of all the actresses I have ever seen, there was never one quite like Jeanne Eagels," while actress-playwright-Academy Award-nominated-screenwriter Ruth Gordon, a friend of Eagels, said of her, "Jeanne Eagels was the most beautiful person I ever saw and if you ever saw her, she was the most beautiful person YOU ever saw."

Kathleen Kennedy, her co-star in "Rain," said, "I sincerely doubt if Jeanne Eagels really knew, in spite of her pretensions, that she was a great actress. She was. Many times backstage I'd be waiting for my entrance cue and suddenly Jeanne would start to build a scene, and [we] would look up from our books at once. Some damn thing- some power, something- would take hold of your heart, you senses, as you listened to her, and you'd thrill to the sound of her."

John D. Williams, the director of "Rain," called her an acting genius. "Acting genius--that is, the power of enhancing a written character to a plane that neither author nor director can lay claim to -- Miss Eagels had at her beck and call, whether in tragedy or in comedy."

- IMDb Mini Biography By: Jon C. Hopwood

More about Moffett Studio:

Chicago's premier venue for visually recording civic culture in the 1910s and 1920s, Moffett Studio began as a partnership between real estate developer Evan Albert Evans and camera artist George Moffett in 1905. Moffett proposed that Evans allow him to construct a studio on the top floor of Evans's property at 57 E. Congress Street, across from the Auditorium Building. Evans ran the business while Moffett manned the camera. The collaboration proved inspired.

Moffett was a versatile lensman, adept at architectural photography, pictorialist visions of nature, home photography, and celebrity portraiture. Evans proved a genius at managing and advertising. In 1907, Evans hit upon a new business model for running the studio. Until that juncture, "newspapers paid large prices for photographs of celebrities or big men of the hour; but Evans started in to furnish such pictures free of charge in order to bring the Moffett name before the public." The strategy paid off in 1912 when the Republican National Convention convened in Chicago and selected the famous Moffett Studio as its official photographer. It became nationally famous and highly remunerative. (Evans would later take over Chicago's Drake and Matzene studios.)

Moffett and his able camera colleague George O. Hinchliffe excelled at elegant portraits in fashionable settings: seated actresses as windows (gesturing at the "home photography" fashionable in Society portraiture), dancers on stone benches, standing vaudevillians amid statuary. Moffett's images were widely published in magazines and newspapers and hugely admired. Moffett Studio developed its interest in theatrical portraits in 1908.

In the latter 1910s, Moffett turned over the theatrical photography to camera artist Paul R. Stone who, though he was not granted credit on images, was allowed to voice expert opinions under his own name in the press. Stone handled the celebrity shoots until Evan Evans turned over direction of the studio to a management team appointed by Underwood and Underwood in mid-1920s. At that juncture he joined Raymor Studios in Chicago, a gallery that ran a diversified business in the city. Rebranded the Paul R. Stone-Raymor Studios they remained an active business from the 1920s through the 1940s. However, the arrest by the F.B.I. of studio employee Earnest D. Wallis for possession of photographs of classified plans for the A bomb in 1947 fatally damaged the studio's reputation.

In the 1940s, Underwood & Underwood sold Moffett Studio to the partnership of Robert T. McKearnan and Jack Russell. McKearnan took over complete control in the late 1950s. In the 1980s it was purchased by Arthur Cournoyer. At that time, the stock of negatives in possession of McKearnan was deposited in the collections of the Chicago Historical Society. The studio still existed in 2012. David S. Shields/ALS

Specialty:

George Moffett and his colleague George O. Hinchliffe shared a penchant for shooting whole figure or half-length portraits done in relatively sharp focus, often in elaborate studio settings. When he produced head shots for theatrical publicity, they were often strong profiles. Images he produced personally were signed in bold red characters. Photographs were signed in the negative with a copyright symbol and "Moffett Studio' in sans serif uncials.

Biography By: Dr. David S. Shields, McClintock Professor, University of South Carolina,

Photography & The American Stage | The Visual Culture Of American Theater 1865-1965